I was chatting with a Linux using, terminal toting, office mate of mine earlier today about Jupyter and its use cases. She contented “Why would I use Jupyter when I can just quickly plot something in the terminal”. Now, I am not often one to push people away from using the command line. However, in this case I think there is a real benefit to using Jupyter. I’m gonna put down some of these thoughts here. If you already use Jupyter then this post probably isn’t for you; however, if you tend to do all your work with scripts and the REPL then perhaps this post will convince you to give Jupyter a try.

First of all I want to define when I think you should not use Jupyter. Jupyter is a visual tool not a software development tool. Therefore, for anything you need to exist as a piece of stand alone software Jupyter is not your friend. Two examples might be a data reduction pipeline and some numerical modeling software (such as a stellar evolution or fluid dynamic program). Let’s think about why we would not want to use Jupyter in the case of a data reduction pipeline (and here I am going to ignore language speed, Jupyter can be used with many languages so it would be reductive to focus on the performance issues of just python). A reduction pipeline is often something you will need to run multiple times, perhaps multiple times separated by a large time interval. Jupyter makes this…uncomfortable… You need to first open the notebook, then run each cell in order. While this is certainly doable it is non idea. Moreover, because it is inherit to the design of notebooks that cells can be run out of order the possibility always exists that you accidentally use some output from a cell latter in the notebook before it is defined. Think of this as a similar issue to that global variables pose when writing code. Moreover, Jupyter does not easily interface well with git, there are ways to make it work, but its not friction-less. For all of those reasons, and in fact many others, whenever you find yourself doing “software-development” steer clear of Jupyter. I a case like this I will always argue for scripts (and in fact scripts tied together in such a way that the user only needs to enter a single command to use them….makefiles for this use will certainly be a post in the future) However, often in astronomy we are not doing software-development; rather, we are investigating data and telling stories about that data. This is where Jupyter shines.

Investigating Data

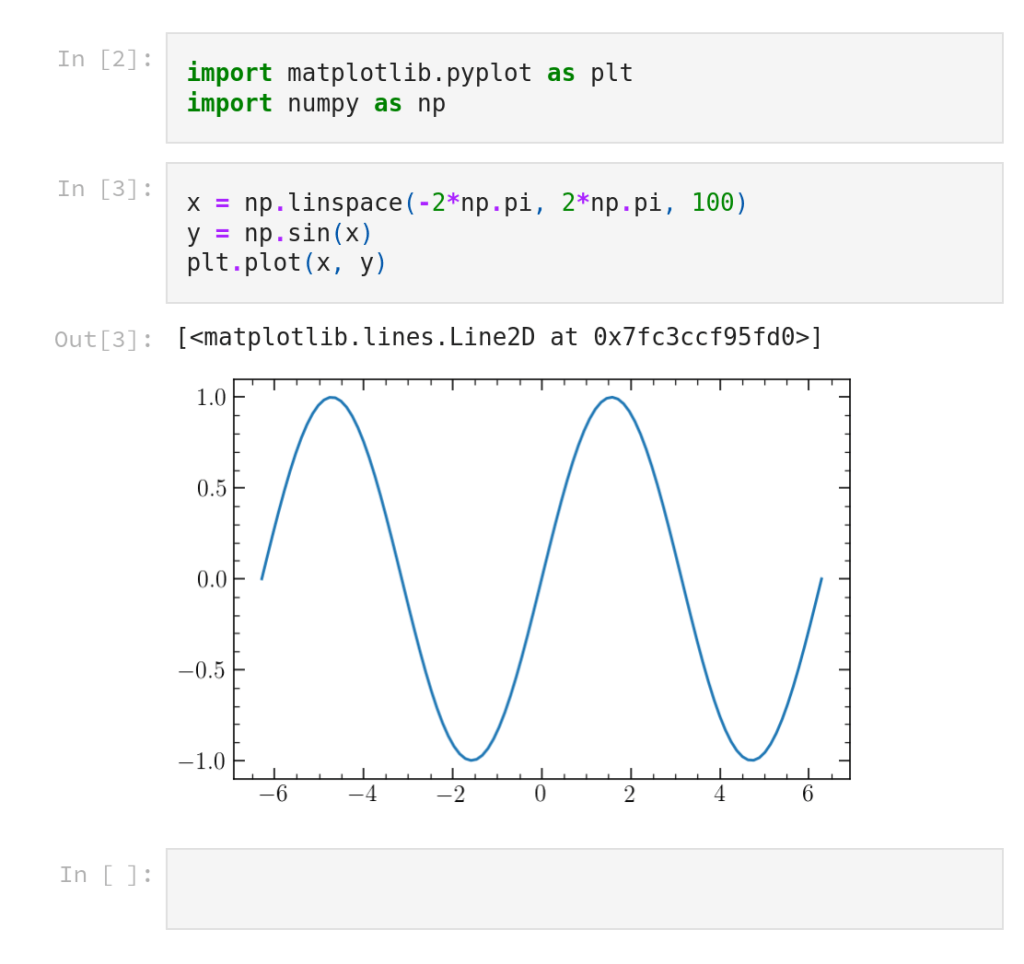

Jupyter provides a graphical environment where code can be run. This means that plots can be embedded directly into the environment. I find that 90% of the time I use Jupyter it is to make a figure or to quickly look at some plot. Recall, this is all an argument about friction, you certainly can write the following code in a script (plot.py)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(-2*np.pi, 2*np.pi, 100)

y = np.sin(x)

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.show()

Then from the shell

$ python plot.py

However, this simply involves more steps than it would in Jupyter (under one assumption, that Jupyter is running, which I will get into latter). You have to open a file, type out the code, run the script, then close the window. Moreover, once you close the window the plot is gone. Now you could savefig; however, in that case you then have to separately open the plot every time you want to look at it. In Jupyter similar code may look like:

Now, by pure code amount this is basically the same (modulo plt.show()/plt.savefig()); however, you do not have to close the figure nor do you have to open a file with the figure within it. More importantly, the figure is persistent, it will be there whenever you open the notebook in the future, and you can plot more stuff in the same notebook while still seeing all the previously generated figures. This is incredibly helpful if you want to investigate how changing parts of your analysis affect figures.

The general takeaway in this section is simple: I have found that, in general, using Jupyter for figure generation reduces friction in enough small ways that overall it saves me dramatic amounts of time.

Now the caveat to all of this is that Jupyter needs to be running its web server. I get around this by keeping Jupyter running on a server at my apartment which I can access when I am VPN’ed into my home network. Obviously, this is not a solution for everyone. So I would suggest one of two things for the curious astronomer looking to sample the ways of Jupyter:

- Run Jupyter as a background service on your computer at all times. Jupyter is not heavy on resource usage so running it in the background should not make any noticeable impact on your computers preference. Then you can just navigate to localhost:8888 in a browser whenever you need it.

- Use the JupyterLab App. This is a desktop application so you can just pin it to your dock/dashboard/task bar and click on it whenever you want to use Jupyter.

Telling a Story

The above is enough for me to use Jupyter, and in fact, 90% of the time I’m using Jupyter is just to make Figures. The other 10% of the time I use it to make presentations. Jupyter uses reveal.js to turn its cells into slides. This is an amazingly useful feature as you can quite painlessly turn the data exploration you were doing above into a nice looking slide show. To be clear, this will not produce the most amazing presentation in the world without effort, but it gives you both a presentation and a notebook which you can follow along in the presentation. A very simple example can be seen here.

I don’t think there is much more to say here. Perhaps in future I’ll do a post on reveal.js and how to make presentations with it and with Jupyter, but for now I just want to bring to your attention that Jupyter has this feature.

Final Notes

A quick note on Jupyter Notebook vs. Jupyter Lab. These are the two main ways to interface with notebooks. Jupyter Notebook is the older interface while Jupyter Lab is the modern interface. At this point there is no reason to use Jupyter Notebook. Jupyter Lab is better in all ways (to be clear it still opens .ipynb files, commonly called “jupyter notebooks” its just a different web app around them). To launch Jupyter Lab you simply type

$ jupyter lab

from whatever directory you want to run Jupyter within.

I hope that if you have not tried Jupyter this post will give you a push to give it a go, it really can make your life a little smoother and easier.